Feedback Loop: Playing To Win

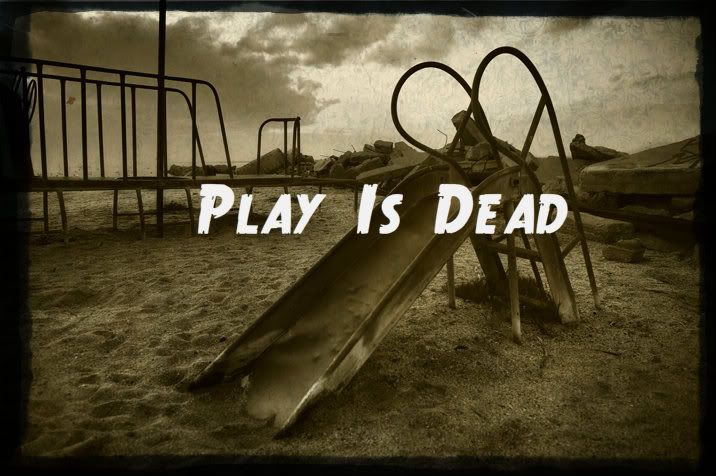

Photograph by Jodi Miller I must be one insufferable little prick. As I navigate the Inception-like hallways of Halo: Reach’s Reflection map, a grin spreads slyly across my face. I’m armed only with a DMR, a score of 49 to 49, and a genuine lust for Blue Team blood. “Hallway’s clear,” signals my friend in a fuzz of chatter. It wasn’t. A blue figure jumps around the corner. My heart hesitates, but my finger doesn’t. The shot stays true. “Competition has one goal: Determine a winner at the end,” writes Brian Campbell for The Escapist. Campbell’s theory about competition and play asserts that intense competition means “the feel of the game becomes far more serious…and less fun.” But is play really divorced from competition? Do they live separately, engaging in a failing long-distance relationship where Play decides there’s too much living to do to stay tied down to sweaty-sounding nouns? In a word: No. It’s an argument based on a term-confusion problem that runs rampant in videogame journalism. Ask five people what videogames are and you might get five different answers: videogames are art; videogames are entertainment; videogames are interactive; videogames are social; videogames are a new form of storytelling. Those five people might not agree on each other’s definitions of videogames, but they may find common ground on the fact videogames are about playing. So let’s avoid the leviathan of subjectivity that videogames are and focus on what play is – an activity of enjoyment. In other words, play is fun. Wow, so videogames are fun; didn’t need a quantum physicist to figure that one out. But instead of asking what fun is, let’s try instead looking at how fun is achieved. In a phrase that would make Dr. Seuss blush, fun is won. So when you look at fun as a goal to be achieved, you’re faced with a competition of some sort. You cannot win anything without competing against something. And since videogames are about playing, and playing is about winning, then videogames are about competing. What you win, however, comes from a staggering number of possibilities, such as fellowship, enjoyment, or championship within the game’s rules. Each of these goals are accomplished through competition. You see now how quickly subjectivity become a thorn in the collective urethra of games writing? Mistaking cooperation for mercy, Campbell theorizes, “Valuing play over competition sometimes means letting someone take back a bad move or recover from bad luck.” Putting forth his own encounter with “cooperative competition,” Campbell recalls a Magic: The Gathering game with a female friend where he didn’t “press the advantage” because “where’s the fun in an ending you already know?” This style of play, he argues, brought out the best in each of them. Playing, Campbell suggests, should be about “how we play without always letting it be why [we play].” But isn’t how we play determined by why we play? When we play for a reason it affects how we go about playing. People play videogames to win adoration; to win fellowship; to win within the game’s rules; etc. So, if playing to win within the rules of the game, how we play becomes more aggressive. If playing to win, say, the enjoyment of company, how we play becomes less aggressive, but only in the traditional sense. Why we play leads into how we play, and becomes the basis for playing. Where Campbell’s subjectivity hits its stride is his assertion that people playing to win the game take the fun away for everyone else. Can’t the same be said about people playing for simple amusement? Let me explain: In 2010 I played Halo: Reach team deathmatch religiously with one of my good friends. Much of our time playing Halo and other first-person shooters involved the “prepare to die” mentality Campbell describes. For the most part, win or lose, I had a blast playing, because the teams my friend and I competed with were also embroiled in a “Die! Die! Die!” style of play. It’s exhilarating — at least to me — to face someone more skilled than I (Darwinian Difficulty, anyone?). I’d go so far as to say it’s fun for me. What isn’t fun, however, is when some jackass takes that competitive spirit of the match and shits all over it by playing for simple kicks. I like a good knock-out and tea-bag as much as the next Spartan, but if you do it to your own teammate again and keep costing us points I’m gonna write an article about you in a few years. “If the motive is more important than the play itself, it’s not play,” said Dr. Stuart Brown in 2008. Campbell puts forth a similar argument: “Are we allowing the competitive ‘spirit’ behind our play to become the competitive ‘phantom’ that overshadows it?” What Campbell failed to take into account, however, was the concept of flow, which Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi defined as “being completely involved in an activity for its own sake.” When in a flow state, however, the motive to win isn’t the motive for play, but a by-product of it. A world without competition is a world without play. WhatCampbell suggests cannot be about toning down the competitive nature of gaming, but rather a matter of common courtesy, of human decency. Because our interests do not, and will not align 100 percent of the time, we should all just accept that eventually someone is gonna sneak up behind us and fuck us right in the fun. |

Great piece! It never occurred to me that competition could essentially be the core of every and any game.

Recently, though, I have played two games that really push the boundaries of this concept, the first being Botanicula, the second being an interactive web “game” titled Bla Bla.

In the case of Botanicula, while there are both short term goals (puzzles) and long term goals (story), it wasn’t often where they felt like competition, let alone “play”. If I could mathematically break down the game I would say that it’s only about 20% play as opposed to 80% “experience”. In other words, the game is mostly about clicking on things just to see what they do, with the reward being the vast amount of fantastic animation. Most of the play, therefore, could be defined as exploration, not competition.The other “game” I mentioned, Bla Bla, takes this concept to the ‘nth degree’ by literally having no puzzles or story or competition whatsoever. I call it a “game” because it is more like “interactive animation”. By most peoples standards this might not be considered a game at all, but if a game is defined by play then Bla Bla is a game. It lets you play around with its abstract visuals and rewards your curiosity with even more abstract visuals.

Thanks for taking the time to respond to my article! This is exactly the kind of discussion I was hoping to get moving. Before we go further, though, I’ll have to correct a couple misunderstandings or misconceptions:

“So when you look at fun as a goal to be achieved, you’re faced with a competition of some sort. You cannot win anything without competing against something. “

Sure! Even the simplest games contain some form of opposition for the player to overcome. I you’ll read my article again, you’ll find that I’m not trying to eliminate competition. I simply question how high on the “totem pole” it should rest. Competition can be a healthy, helpful thing… but like any hungry beast, it can also have a tendency to eat more than its fair share. It could occasionally benefit us all to rein it in.

“Mistaking cooperation for mercy, Campbell theorizes, “Valuing play over competition sometimes means letting someone take back a bad move or recover from bad luck.””

Mercy IS cooperative, in its very nature. What purpose does mercy serve for the individual showing it? Little or none, really. We show mercy because we recognize that such things can benefit ALL of us. We show mercy because it allows mercy to continue existing (so that one day we can benefit from it, too).

“Playing, Campbell suggests, should be about “how we play without always letting it be why [we play].” But isn’t how we play determined by why we play?”

Yes, it is. But (if you’ll take another look back over that quoted portion) I’m speaking about Competition. In the article, I make the clear statement that competition is nearly always a part of HOW we play a game. It’s in the mechanism. Now, if we promote competition to WHY we play, your statement is very correct: it determines a lot about how we play that game.

When competition is the (capital W) “Why” we play, the other players are knocked to second place (or lower). That means when we come upon a choice, and one option serves The Win, and the other option serves The Group, we’ll be choosing to serve The Win. Because that’s Why we’re playing, after all.

“Where Campbell’s subjectivity hits its stride is his assertion that people playing to win the game take the fun away for everyone else. Can’t the same be said about people playing for simple amusement?”

Here’s the difference: When you “play to win,” the other player is an obstacle… but they’re a necessary obstacle. They need to be willing to get chewed up in your war machine in order for you to win. In a very broad sense, you’re using them to generate fun for yourself. (And in many groups of friends, that works! I’m not saying it should be ‘verboten’ for everyone, just that it shouldn’t be assumed).

When someone is playing for enjoyment with friends, they’re not taking away from others. They’re making sure other folks are having fun, too. They’re GIVING to the group, and often giving up the easy points.

The example you’ve presented – someone teamkilling for kicks in Halo – is not even the slightest bit what I’m talking about. That’s a different sort of “fun at someone else’s expense.” In fact, it demonstrates pretty clearly exactly what I’m talking about: certain playstyles actually take fun away from other people. That Joker-esque “world burning” type of play is just another form of the exact same mentality, in which the focus is on “me getting what I want,” regardless of how it affects you.

“What Campbell failed to take into account, however, was the concept of flow, which Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi defined as “being completely involved in an activity for its own sake.” When in a flow state, however, the motive to win isn’t the motive for play, but a by-product of it.”

Which is precisely what I’m aiming for. There’s a certain amount of reading-in that you’ve brought to your understanding of my original article, which is what I’m hoping to correct here. Winning, here defined as “the ending condition of a game in which a victor is named,” is a necessary part of most games (or all competitive games). It’s something that must happen in order for the game to reach an ending.

For some people, that end condition is the Why. They want the win, meaning the whole experience in between is an obstacle to that. Other people love playing, or enjoy the time with friends, and they’ll occasionally put aside the quick win to prolong the experience – to keep the Flow going.

In my article, I’m simply speaking out against the former: people who want the Win more than they want to Play. Nothing wrong with winning. Nothing wrong with wanting to win. And in some situations, there’s nothing wrong with the take-no-prisoners style of getting to the win as quickly as possible. But not all the time.

You’re right that we’re not all going to agree 100% of the time. Competition is important, it can be healthy, and it can be a lot of fun. But it’s not the only way to play. And even competitive gaming can BENEFIT from keeping things a little less cutthroat.

(Why am I coming down so hard against overly-competitive play, and not decrying the evils of the anti-competition side? Because of the two (cooperation and competition), competition is the one that’s more likely to get out of hand, am I wrong? When has a war been raging, and suddenly a Peace breaks out with nearly no warning? Cooperation takes a bit more work and attention, so that’s where I’m focused. Competition will always be there, and it can take care of itself.)

“If you’ll read my article again, you’ll find that I’m not trying to eliminate competition. I simply question how high on the “totem pole” it should rest.”

I did get what you were saying with your article, and your response here is exactly the reason for my response. I’m not saying your stance is wrong, but that competition isn’t relegated simply to playing to win within the rules of the game. Rather, competition is a necessary component of achieving ANY goal when a person begins to play, whether that goal is to win the game through highest score or just to enjoy a few laughs. Both are goals, and both rely on competition in order for that goal to be achieved. In the sense of “winning” laughs as a goal, the competition is not necessarily against the other player, but against his current state of being, the nature of the particular game’s design and, yes, even against the other player if that’s what it takes (like my Halo example).

“Mercy IS cooperative, in its very nature. What purpose does mercy serve for the individual showing it? Little or none, really. We show mercy because we recognize that such things can benefit ALL of us. We show mercy because it allows mercy to continue existing (so that one day we can benefit from it, too).”

True, if we assume all acts of mercy are for mercy’s sake then it is essentially working toward the common goal for mercy to continue to exist. But that doesn’t solve the “fun” issue. It’s still the same princple of “limited resources” you defined: one person is going without in order to benefit the other person, because as you just said mercy serves “little or none” to the person showing it.

A cooperative effort in the act of playing, however, would serve to facilitate each player’s goal during that play session. We can’t assume that if one person loses then he didnt have any fun. So, mercy, to the person playing for the enjoyment of pure competition, would actually diminish his fun, because he didn’t find the exhilaration of true competition he was looking for.

“When competition is the (capital W) “Why” we play, the other players are knocked to second place (or lower). That means when we come upon a choice, and one option serves The Win, and the other option serves The Group, we’ll be choosing to serve The Win. Because that’s Why we’re playing, after all.”

But “The Win” could come from simply playing with a group of people in a game without a win condition; i.e. playing to “win” a state of mind better or different from the one the player began in.

“Here’s the difference: When you ‘play to win,’ the other player is an obstacle… but they’re a necessary obstacle. They need to be willing to get chewed up in your war machine in order for you to win. In a very broad sense, you’re using them to generate fun for yourself. (And in many groups of friends, that works! I’m not saying it should be ‘verboten’ for everyone, just that it shouldn’t be assumed).”

I agree. But my piece is about showing there are multiple kinds of competition. When you play you have a goal in mind, and that goal is competed for in order to be won. The goal can differ, as can the competitive nature. My gripe with your piece was that you only used competition in that one sense, so I wanted to show that competition is not seperate from play but is involved in the very DNA of play, at every level all the time.

“I’m not saying your stance is wrong, but that competition isn’t relegated simply to playing to win within the rules of the game. Rather, competition is a necessary component of achieving ANY goal when a person begins to play, whether that goal is to win the game through highest score or just to enjoy a few laughs. Both are goals, and both rely on competition in order for that goal to be achieved.”

I think I’m starting to see what you’re saying. It’s a bit more esoteric than I was aiming for — I was intending to offer simple, practical advice for folks that have run afoul of the dark side of competition. Basically, I’m only speaking on the notion of player-versus-player competition. Every game contains player-versus-game mechanics, obviously — even if it’s as simple as learning the control scheme.

When I play Checkers, I’m competing against my opponent. It’s HOW you play checkers — I move based on what will position me to eliminate my opponent’s pieces, and s/he does the same.

But it’s just the mechanics of play that are competitive. That doesn’t have to be the REASON I’m playing. It might be to try out some new strategy and see whether it works or not. It might be an excuse to hang out while drinking a beer and catching up. Just because there needs to be a winner doesn’t mean that needs to be the most important feature.

“…if we assume all acts of mercy are for mercy’s sake then it is essentially working toward the common goal for mercy to continue to exist. But that doesn’t solve the “fun” issue. It’s still the same princple of “limited resources” you defined: one person is going without in order to benefit the other person, because as you just said mercy serves “little or none” to the person showing it.”

Mercy is cooperative. I did not, however, say that all acts of “cooperative competition” equate to “mercy.” That’s an aspect of it, sure, and it’s one way to practice “cooperative competition.” But it’s also just a matter of priority. It’s about choosing what keeps the game fun, what keeps the game going, instead of choosing what puts you ahead on the scoreboard. Now, it’s not always one or the other, but it comes up pretty often.

“We can’t assume that if one person loses then he didnt have any fun. So, mercy, to the person playing for the enjoyment of pure competition, would actually diminish his fun, because he didn’t find the exhilaration of true competition he was looking for.”

We can reason, however, that many people have LESS fun when they lose. And, if they were stomped pretty hard and don’t feel they ever had a chance, that effect is multiplied. As to the person “playing for the enjoyment of pure competition,” there are TONS of outlets for them, like tournaments.

The problem is that in a group of friends, all it takes is ONE person to be the “play for pure competition” guy, and it changes the game for EVERYONE ELSE. It’s like the guy that brings a fire hose to a water gun fight. Sometimes it’s okay, but other times the GROUP has more fun if it’s a little less cutthroat. Save the “pure competition” for the tournament, and don’t always treat your friends like “tournament practice.”

“But “The Win” could come from simply playing with a group of people in a game without a win condition; i.e. playing to “win” a state of mind better or different from the one the player began in.”

Again, that’s outside the scope of what my article was saying. When I’m talking about winning, I’m talking about satisfying the win conditions of the game. The reason I may seem a bit lost is that you’ve billed your article as a COUNTER to mine, but it really feels like you’re countering stuff someone else said…

“But my piece is about showing there are multiple kinds of competition. When you play you have a goal in mind, and that goal is competed for in order to be won.”

This is where I think the confusion sets in. We’re getting into a terminology loop. What you’re calling “competition” isn’t really competition in any literal sense. Competition only takes place when two parties are going after something only one of them can have. If both parties can have it, it’s not competition. If only one party wants it, it’s not competition. Not every situation that involves facing OPPOSITION is a competition.

“My gripe with your piece was that you only used competition in that one sense, so I wanted to show that competition is not seperate from play but is involved in the very DNA of play, at every level all the time. ”

And that’s the crux of it. I don’t disagree with the CONCEPT you are putting forward. In fact, my article is about exactly that — there’s plenty of reasons to play other than JUST to win. But I disagree that we can just use the word “competition” as loosely are you’ve offered.

When I’m working on a puzzle, it requires effort and thought, sure. But I’m not “competing” with the puzzle. I’m “overcoming challenge,” maybe even “striving.” If I was trying to beat someone else’s time for completion, NOW it’s a competition — two people want the “best time” spot, and only one can have it.

This definition of competition isn’t of my invention, either. It’s how the word is defined, and has been for a long time. It’s not challenge or goals that define a competition, it’s the fact that two or more sides are after something that only one can have.

I never said competition needs to be the most important feature, but that competition is an integral part of playing. If you are playing for fellowship as you just described (and as I also described in my piece) then the competition may not be with each other. But that’s not to say that it can’t be. For instance, I may go out drinking with my buddies with the goal being to have an awesome night. Afterwards, I might talk about how wasted I was or how many numbers I got, etc., with the implication being I had the most fun.

Similarly, competing in the traditional sense you are talking about doesn’t necessarily mean that being the winner is most important, especially if we take into consideration one player being “stomped pretty hard” by another player. It’s safe to assume then that the player handing out the stomping is pretty secure in his win, therefore simply winning the match isn’t a motive at all – he’s just showing off.

It’s not that I don’t see what you’re saying. I do. That’s why I say in my article what you’re talking about isn’t about toning down the competition but simply a matter of decency.

“When I’m working on a puzzle, it requires effort and thought, sure. But I’m not ‘competing’ with the puzzle. I’m ‘overcoming challenge,’ maybe even ‘striving.’”

Exactly, competing is DEFINED as striving for an objective. So, yes, you (the first party) are competing against the obstacles of the puzzle (the second party) in order to secure “the business of a third party.” Now we can argue the puzzle has no actual want for the third party because it’s inanimate, but it is still presenting obstacles keeping you from that third party, which is what competitors do.

So I don’t disagree with how competition is defined, but how you imply competition is separate from play. What you tried to do is to rigidly define something within the subjective parameters of videogames. Confounding this is your prominent use of “we” and “us”, insinuating your values of what is fun and what is not are shared and agreed upon with the audience. They are not. If we say it’s necessary to tone down the “competitive spirit” in order to get back to enjoyment, then that would mean the competitive spirit only leads to bad results. It doesn’t. That’s why there are terms like sportsmanship; which isn’t to say “be merciful” but rather “don’t be douche bags.”

It’s clear now that you’re reading in a lot that isn’t there.

For one, competition is not defined as “striving for an objective.” Competition is defined as “rivalry between two parties for something that both parties want.” Rivalry. Both parties want. Those are the defining features of competition. You can’t just reinvent words, I’m afraid.

“So I don’t disagree with how competition is defined, but how you imply competition is separate from play. ”

Actually, yes, you do. You’re altering the definition of competition to an unrecognizable state. You’re trying to force it to be synonymous with play, so that you can then insist it’s an integral part of all play. I’ll agree that it’s an important aspect of play, in the same way that a ball can be important to play — depending on the game. Not all games use a ball, not all play is competitive.

‘Confounding this is your prominent use of “we” and “us”, insinuating your values of what is fun and what is not are shared and agreed upon with the audience. They are not. If we say it’s necessary to tone down the “competitive spirit” in order to get back to enjoyment, then that would mean the competitive spirit only leads to bad results. It doesn’t.”

It’s no less confounding than your insistence that everyone adopt your heavily-personalized definition of “competition.” What’s more, I was very clear that competition doesn’t “only lead to bad results.” There are potholes along the road, and if we’re not careful of them, we can HAVE bad results. But I’ve been very specific about those hazards, and that competition itself isn’t a bad thing.

As to “we” and “us,” I’m not being the absolutist here. There are right many of us who have been in situations where overly-competitive players in a group ruin the fun for others. This is presenting some ideas to those people who see it as a problem. If someone doesn’t see a problem, it’d be silly for them to look for a solution. The idea I’m presenting isn’t being pushed as some golden solution that works for everyone.

Your idea, however, is being pushed as a complete ground-up redefining of a long-existing term that has a very clear meaning. That presents some pretty hefty barriers to communication. Without your needless discarding of the actual definition of “competition,” all that’s really being said here is, “All games have obstacles.” And no one disagreed with that, so this is just barking at the wind.

My definition was taken right out of Merriam-Webster, where it defines competition as “the act or process of competing” and it defines competing as “to strive consciously or unconsciously for an objective (as position, profit, or a prize)”.

Ah, you mean this definition which you’ve conveniently cherry-picked from?

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/competition

“1: the act or process of competing : rivalry:

a : the effort of two or more parties acting independently to secure the business of a third party by offering the most favorable terms

b : active demand by two or more organisms or kinds of organisms for some environmental resource in short supply”

“2: a contest between rivals; also : one’s competitors <faced tough competition>”

And the definition of “compete,” in which they make it pretty clear they’re talking about rivalry. After all, here are ALL of the same sentences:

“Thousands of applicants are competing for the same job.

She competed against students from around the country.

We are competing with companies that are twice our size.

Did you compete in the track meet on Saturday?

The radio and the television were both on, competing for our attention.”

See, prizes, positions, or profit are items such that only one party can get them.

If you guys are struggling about definitions, looking at the etymology may help:

Compete:

1610s, from M.Fr. compéter “be in rivalry with” (14c.), or directly from L.L. <b>competere “strive in common,” in classical Latin “to come together, agree, to be qualified,”</> later, “strive together,” from com- “together” (see com-) + petere “to strive, seek, fall upon, rush at, attack” (see petition). Rare 17c., and regarded early 19c. as a Scottish or Amer.Eng. word. Market sense is from 1840s (perhaps a back formation from competition); athletics sense attested by 1857. Related: Competed; competing.

The bold makes a particularly good amount of sense. Competition and Competence as extremely interrelated. Competence implies skill, so anytime one is trying to apply his skills to get an achievement or improve their time, one is fighting oneself. So sometimes only one party is enough, rivalry doesn’t imply more than one person.

For groups, however, the notion of competing doesn’t necessarily equal a win-lose scenario. The whole field of Game Theory can attest to that.

The problem, however, is that you guys are using the term to determine something incredibly subjective as “fun”. Fun can be any shit. It can be won, it can also be struggled or even received freely.However, it makes sense to point out that the entire notion of Gamification derives from the hypothesis we have more utility (read: fun) when we get something after fighting for it rather than simply receiving it freely (i.e. you get a store discount after reaching “client level 3” rather than simply receiving it).

How much is the perfect amount of struggle is ideal? That depends on you and you alone.

@dastardly

I havent’t deviated from that definition once. Play is an action set in motion by an objective, i.e. to have fun. In order to win the objective (the third party) one party competes against a second party. As I said in my comment before last, the second party can be the obstacles the game throws at you.

Play IS competition. Always. And as I’ve been saying, fun is subjective. You assert that lessening the competition will get us back to playing and having fun and you use a player getting “stomped” by another player as your example, suggesting the playing doing the stomping should show mercy to the other player. So assume he does show mercy and gives the other player a chance to have fun, then we can conclude he is having less fun because he is not getting the play experience he wants. What makes one person’s fun more valuable than the other?

FRPCORDEIRO:

Definitely consulted the etymology. When you equate “competition” to “competence,” you’re discussing an archaic meaning of “competence” that is never used today. The only things the two share in common are the portions that mean “strive together.” The defining characteristic of competition is rivalry, even down to the etymology.

As to the idea of fun, that’s exactly what my original article put forward: some people have fun through intense competition, some people prefer cooperation, but it’s not always about segregating the two. When the two meet, usually the “intense competition” part dominates, and that ensures that those folks get ‘more of the fun’ than the folks that like things less cutthroat.

I’m talking about finding a way to share a competitive experience in a way that is enjoyed by both sides equally. Competition is still going on, and there’s still a winner and a loser, but we occasionally put aside the cutthroat tactics in the interest of playing a bit longer and making the game more interesting. (Usually, this means toning down the intensely competitive aspects, because those are more apt to intrude on others than the cooperative stuff. That may be why some people wrongly feel I’m coming down against competition.)

As to the current discussion, I really relish the idea of fleshing out the difference between different playstyles. It’s just that right now, the discussion is bogged down in a gross misuse of a particular term to mean something it does not. Unfortunately, it’s making it look less and less likely that the author was disagreeing with what I actually wrote, but rather disagreeing with a misunderstood perception.

ARTISIN:

Obstacles are not rivals. Obstacles are just things that impede my progress. To say I’m “competing” with the goombas or the holes in a Mario game is like saying I’m “competing” with a door every time I open one to get into a room. Now, if someone were pulling on the door from the other side, THAT is a competition — only one of us can achieve our goal. Or if I were racing someone to the other side of that door — only one of us can be first.

But again, my article is about those situations in which one PLAYER is competing against another PLAYER. That’s the kind of competition I clearly laid out. So even allowing the esoteric concept of “everything is competition,” it’s outside the context and scope of the article. We’ve got to move past this terminology snafu if anything productive is going to come of this exchange.

For instance, I can work with this:

“You assert that lessening the competition will get us back to playing and having fun and you use a player getting “stomped” by another player as your example, suggesting the playing doing the stomping should show mercy to the other player. So assume he does show mercy and gives the other player a chance to have fun, then we can conclude he is having less fun because he is not getting the play experience he wants. What makes one person’s fun more valuable than the other?”

Indeed. What makes one person’s fun more valuable than the other? What gives the “Stomper” the right to go up against an outmatched opponent (the “Stomped”)? See, the question runs both ways. Which is why I’ve proposed we find a middle ground.

A “stomper” player can find tons of outlets for that kind of play. Tournaments are one of the best. There’s a time and place for that kind of play, as I mentioned in the article. It’s just not ALL times and ALL places. When a group of friends includes a “stomper,” often the game ends in favor of the stomper… but that’s not the problem.

The problem is when the game ends faster because of the Stomper. Or when other players feel like they didn’t really get to play. Or when the tone of the game changes from fun to serious. One person’s fun can, in these situations, take priority over everyone else’s — which, by your own admission, is clearly a problem. Instead of telling the Stomper not to have fun, we might just recommend a different kind of fun.

In these situations, we might ask the Stomper to relax a bit. Maybe don’t use your three-second-victory strategy. Maybe back down from a rules argument. Maybe, when you’ve got the chance to end the game decisively, taunt the other players with it… but then keep the game going, just to see what happens.

And you know what? The Stomper will become a better Stomper for it, too. When you outclass all of your opponents, you win easily all the time. (Or when you take it way more seriously than they do, it’s easy to seem like you’re outclassing them) You learn nothing from that. But working from a slight disadvantage or handicap? Or letting the game go into new territory, outside of your own comfort zone? Those are the things that make you better prepared to handle the “real” competition later on.

You’ve wrongly assumed that someone like our Stomper can only have one kind of fun — the kind that comes at someone else’s expense. If that’s the case, his problem isn’t that he’s a Stomper. It’s that he’s selfish, and a bit of a dick.

(Incidentally, you can see that kind of person rise to the surface whenever there’s a PVP mechanic in a game that fails to adequately “punish” the losers…)

“Play”, in a more general sense, is often about having no stated goal at all. The lack of a stated goal is essential for this kind of play. (For a great description embedded in a somewhat tangential subject, watch John Cleese’s amazing talk on creativity: http://vimeo.com/18913413. Jump to 6:58 for a quick primer on the difference between play and non-play, though it’s worth watching the whole video.) This is quite the opposite of competition.I don’ think it’s a stretch to say that play in video games is related to the more general kind of play, especially with the popularity of “software toys” like The Sims and Minecraft. I think it’s an oversimplification and a misunderstanding of play (and “fun” by extension) to say that all games are about competition and winning. That’s a reductionist mindset that seems a bit convenient given the predominant types of video games being made in the mainstream.Intense competition is more like the “closed” state that Cleese talks about. Rather than describing all games as using this kind of interaction, I think it’s more correct to recognize that goal-oriented and non-goal-oriented fun are both useful tools that should be employed consciously when designing, rather than by accident.

@patchwork_doll

This line of thought is exactly where my original article was headed. Basically, our Play has got a bit too fine a “point” on it… when, as kids, our best play was the kind that was basically pointless.

What I was aiming to do with Cooperatively Competitive is introduce a bit of that way of thinking into our competitive play, so that we can have that freedom and joy even within competitive gaming. In a sense, the Win/Loss decision is just letting us know when play time ends… so, what if we don’t WANT it to end right then? We can put off the winning or losing and spend some more time enjoying the play.

And that’s what it really comes down to: Enjoying the Play, not just the Game.