Multiplicity and Identity Mitigation in Video Games

|

Where before we traditionally thought of identity as a monolithic construct, modernity demands recognition of multiplicity and fragmented identities. Okay, that’s a mouthful, what the heck am I saying? Well, think about how people with multiple identities are more likely to be considered to be ill. That line of thinking–the one that determined, somewhere down the line, that “sane” people have a single, normative identity–is changing. People are asking questions. Where do we end? Where do we begin? What, in other words, is happening to our identities? Using multiplicity and fragmentation as a backdrop, this essay aims to analyze modern video games such as Mass Effect which encourage users to manifest their identities fluidly within their virtual worlds. Though societal institutions struggle with the concepts of multiplicity and identity fragmentation, video games which are considered ‘complex’ and ‘serious’ encourage the players to embrace these ideas. In fact, multiplicity and identity fragmentation could be said to be at the heart of the mechanics and game play within these video games. For example, you can play Mass Effect however you want, even if the actions you take do not correlate with actions you took earlier. However, identity mitigation can only go so far without the establishment of a conceivable game world. As such, we will also spend some time analyzing how well video games can manage to immerse players within the game world in relation to how they manifest their identities through the medium. Click on past the jump to read more!

Normative Identity Though difficult to explain, there is certainly a “normal” conception of identity. I cannot take it upon myself to describe what identity is, but there are various ideas–psychological, legal, etc–which describe how identity is manifested. Stone writes that “most people take some primary subject position for granted. For all intents and purposes, your “root” persona is you. Take that away, and there’s nobody home”. This idea of a root persona–a root identity, if you will–is one that society at large prescribes to. I am considered one person–Patricia Hernandez. That’s who I am, legally or otherwise. Stone goes on to say that “in the social sciences symbolic interactionists believe that the root persona is always a momentary expression of ongoing negotiations among a horde of subidentities, but this process is invisible both to the onlooker and to the persona within whom the negotiations are taking place”. That is to say, identity is not actually monolithic: it is fluid. This rings particularly true to me, a person that spends a good deal of her time online. There are quite a few number of sub-identities I often call into play depending on the situation or location. I am a “different person” when in an online forum where I am an administrator, from the “me” that plays video games online, from the “me” that exists in real life. If I am playing the extremely testosterone-driven Gears of War, I tend to adopt a very threatening, abusive demeanor. If I am playing the cooperative Battlefield, then I try to seem like the tactical leader. And if I’m just in a chat party with my Xbox friends, I’m always very cheerful. All of these are certainly me at any given time, they’re just not me all the time, and I don’t even notice when my “root” is negotiating between all these subidentities. As such it came to be a shock when I met one of the users from the forum that I administrate in real life. The “I” he knew online is certainly me, but that part of me isn’t immediately visible to him. There were many comments regarding how I wasn’t at all how he imagined me to be. But even this “me” in the real life, it’s not really who I am. It’s a mask like any other; it’s who I am at that moment. And so, for someone to meet me in real life and deem this to be the more accurate me is misleading. Steven Shaviro writes that “anyone you meet online is playing a role, adopting a persona; but isn’t this the case when we meet in RL as well? It’s not that I know you less well in VR, but that I come to know you in a radically different way”. Video games are capable of acting as proxies for our identities, and there are three major ways in which video games mitigate identity. For all intents and purposes, they tend to err on the more “practical applications of data compression” meant to depict “an extremely complex, highly detailed set of behaviors” which then unfortunately become “a single sense modality, then further boiled them down to a series of highly compressed tokens”. In short, the extremely complex idea of identity is broken down into a completely computational, legible form. It becomes almost a science. This is in contrast to real life, where “humans have the ability to creatively present themselves in a fluidly nuanced and dynamic way, seamlessly varying gesture patterns, discourse structures, posture, fashion and more, often with an astounding sensitivity for context. Humans are also quite aware of the perceived appropriateness of particular ways to present ones self in different situations”. Of course, boiling identity down to a science seems congruent with ideas regarding “normative” identity. Fox Harrel lists the ways in which video games mitigate identity as “Attributes which are reduced to numerical statistics, social categories are reduced to graphical models and skins plus numeral statistics, and character changes and narrative progress in many popular genres of computer and video gaming are often driven primarily by: combat, spatial exploration and object acquisition”. Identity in Super Mario Bros.

In older video games, players often had no control over the identity of the person they were commanding. Understand, this observation is not a criticism, it is simply…an observation. For example, In Super Mario Bros, the player controls an avatar of a male Italian plumber whose goal is to save his love interest, Princess Peach. Princess Peach has been abducted by his arch-nemesis, Bowser. You cannot change Mario’s name, his appearance, and you cannot explore or otherwise inform Mario’s motivations. You cannot do anything except control Mario, and even this is limited to a few select things. Mario can only go forward or backwards, jump, kill baddies, or collect coins, stars or other powerups. These are all game design choices which restrict what a player can and cannot do within Super Mario Bros. In limiting what a player can and cannot do, game designers effectively force a player to perform the character of Mario–and only Mario. There is a link between his actions and purpose, and the game design accurately reflects what that purpose is: to get through all the obstacles in order to get to Princess Peach. As such it becomes clear that allowing the player to manifest themselves in the game isn’t really the vision game designers had. Nonetheless Mario barely functions as a “person.” The only connection we can make to a real human being is that Mario is probably what a human being would look like if we were to represent a person in 8 bits. Otherwise, Mario could just as easily be a square which we can control, and nothing would be lost. Super Mario Bros does not take it upon itself to try to mitigate the identity of the player–not that it has to, of course. In fact who is playing doesn’t even matter, because you’re controlling Mario and Mario wants to save Princess Peach (assumably). Because Mario has a predefined, albeit simplistic goal, the player doesn’t have to come up with motivations to play the game. A game like Mario doesn’t even have to be believable in order for it to immerse the player. You play the game because of its enjoyable gameplay. Here, Mario’s identity and goals don’t really matter–the narrative is just an excuse to justify why a player would want to navigate their way through various dangerous platforms which may well end up on Mario’s death (an excuse for “fun,” which is, of course, completely understandable). The story is not nearly as important as the game play. This is especially evident when one considers that there is almost no dialog or exposition which tells the player what the story is–we only know the story because the game manual explains it. Nonetheless you can still pick up the game, sans manual, and play it without missing anything important. So while you aren’t Mario in a technical sense, you still control what his actions are on the screen, and so in that sense you really “are” Mario. The player is the very means through which Mario fulfills his limited identity. In a way, Mario acts as a “blank slate” for players. Game designers avoid giving him more layers – thus making him an avatar more able to “merge” with different types of players. They don’t have to give Mario an identity because you will do that job for them. Regardless, it is evident that a game like Super Mario Bros does not take a particularly sophisticated approach to mediating a player’s identity in the game. His professed identity is driven by combat, spatial exploration and object acquisition. Mario’s identity is set into stone.

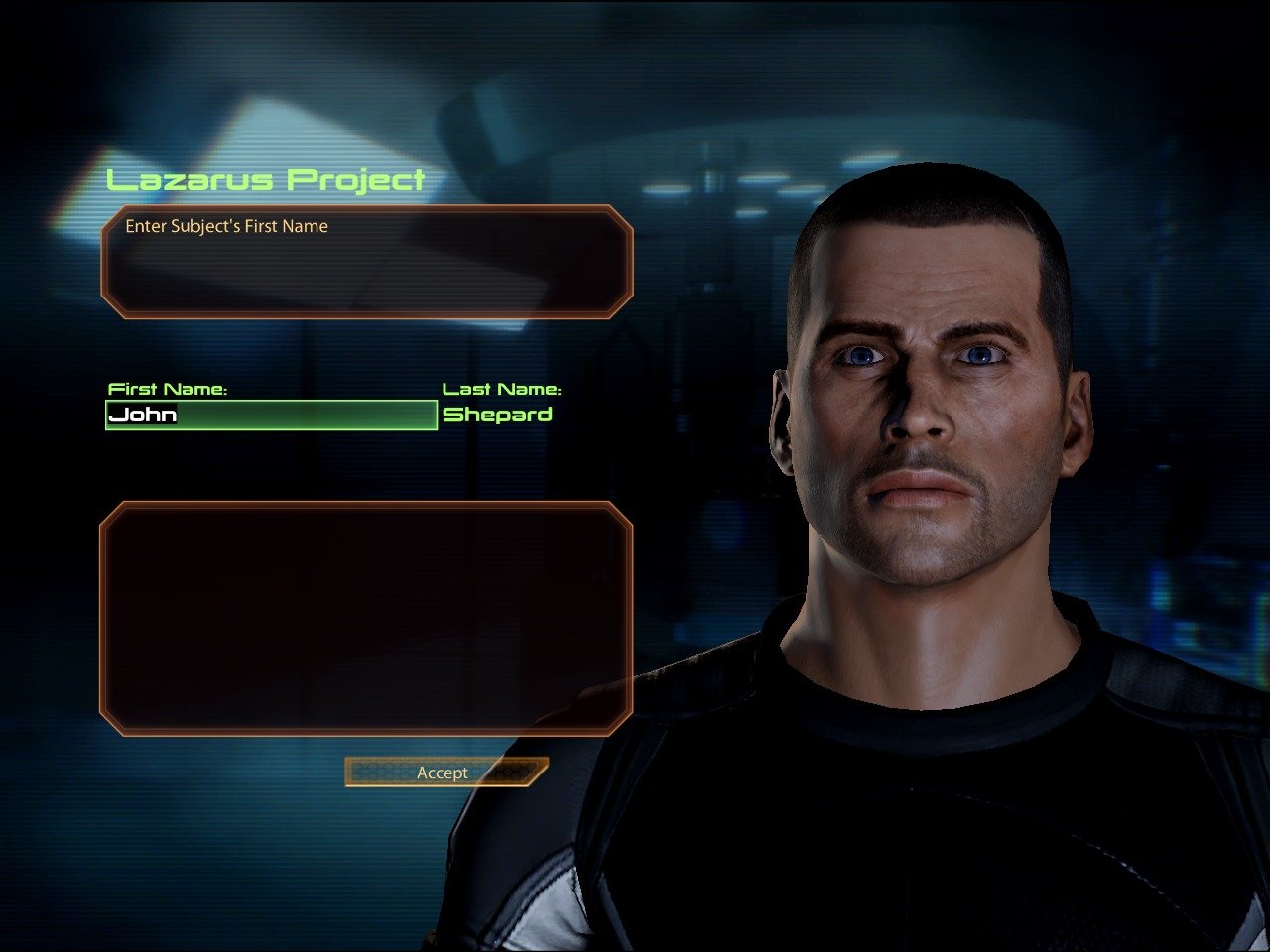

Modern Approaches to Mitigating Identity in Video Games Some modern video games, on the other hand, take it upon themselves to deliver complex narratives with a high degree of interactivity meant to emotionally engage players. Where perhaps Mario’s approach to identity could be attributed to the limited technology of the time, or even a different design vision, games like Mass Effect 2 believe that in order for a deep level of meaningful engagement to occur, the player must actually feel like they are being represented in the game. The player must feel as if they are manifesting their own identities, and not that of whatever the writers decide. This shift seems to appear concurrently with the technology’s ability to better visually represent what a human being looks like more accurately than before (though certainly, video games are still a ways off from reaching complete visual realism). As such, the video game industry has recently seen a surge of games which allow players to put themselves in the games that they play, both visually and ideologically. Mass Effect 2 tells the story of Commander Shepard, an extraordinary human which catches the attention of an alien council. This council has the ability to appoint “Spectres” an elite group not unlike Jedi. Spectres have the ability to go above the law in order to fix any given situation. While on a mission for the Council meant to determine whether or not Shepard can become a Spectre, Shepard finds out about an ancient race’s plan for an intergalactic holocaust. The premise of the game is Shepard’s adventure to not only defeat the intergalactic threat, but to convince society that this threat even exists in the first place. The player has immense control over Shepard’s visual identity amidst this story. When I start a new game up, I can decide what gender, first name, head type, body type, skin color, hair, ears, nose, chin, jaw, eyes and armor Shepard has. Most of these choices have no bearing over the game itself, they are mostly just meant to give the player the ability to either depict themselves in the game or to simply create a character that they want to role play. In short, these choices are merely cosmetic. Still, cosmetic choices are important: often, when we want to depict a fundamental change in who we are, we defect to the idea that we should change what we look like. Get a haircut, change the wardrobe, get a piercing: changing what we look like, determining how other people see us plays an important role in how we mitigate identity in real life. The choice of gender, however, determines what love interests are available to the player. All love interests have a set sexuality, and if the player is not the right gender, then the player does not have the ability to romance that character. This is a social construct which finds its way into the game, perhaps subtracting the game’s ability to allow players to explore their identities in a safe, accepting space. Armor changes that bonuses the player gets in combat (which is essentially an aspect of identity which is reduced to a numerical statistic). In short, these visual aspects of mitigating identity mostly function to further social categories existing in real life.

The player also has immense control over the various nuances of the story. Though there is a skeletal framework for the story, the narrative is fluid and complex. Major events in the game are predetermined, but the details under which these events occur are completely up to the player. Unlike Mario, Shepard talks. Not only this, but the player can decide what Shepard says. For any given moment in a dialog, the player has up to eight choices of things to say (and any one conversation may hold dozens of different outcomes and opportunities, depending on what the player says). These dialog choices are all related to the subject at hand, but they reflect distinct approaches that a player might have for any given situation (renegade vs paragon). The player can choose to be tactful, agreeable, savage, cold, evil–just about anything you might feel like. The characters on screen you are interacting with will take those cues and react accordingly: if you are too hostile with a thug, he may become violent and attack you. If you are kind to the poor scoundrel, he may just reward you later in the game for being benevolent. Every action in the game has a consequence. You are accountable choices you make, and there are a plethora of decisions which call upon your ethical and moral judgement in order to solve them. In this sense, Mass Effect 2 resembles a choose-your-own adventure book. The beauty of the game lies within the choice given to the player. Who Shepard is by no means set into stone, though you are required to pick a general back story for Shepard to have. In Dragon Age, this back story influences how other characters see or interact with you, and ultimately make the game have social categories within its own lore. For example, if you chose to be an elf, members of society are more likely to see you as scum. There are comparable experiences in Mass Effect, though they are often to a much smaller degree. Regardless of the player’s chosen back story, it is up to the player to define who their character. Just because Shepard’s back story is described as a previous gang member, for example, doesn’t mean that you have to play Shepard in any particular way. I can choose to give my money to a slave to buy their freedom, and in the same play through choose to kill off an entire race. The two actions of this Shepard are reflective of very different personalities, but I am still considered a singular person. I just happen to be a person that can take very dichotic actions–a person that can embrace their multiplicity. Giving this level of interaction to the player allows game designers to flesh out a truly engrossing experience for players. Shepard is defined through all the decisions that I make throughout the game. In doing so, the game itself can become more meaningful for players because you aren’t just controlling some arbitrary actions of an avatar on screen. You are actually playing out and exploring the complexities of not just the story, but of who you are. You aren’t just a spectator in the game; you are the game. You are the means through which the story develops–or doesn’t. In Mass Effect 2, the player can make choices which may result in Shepard failing his mission, dying, or otherwise killing his crew members. In short, the control bestowed to the player allows the player to more accurately depict their own identities within a game.

Still, Mass Effect suffers from very major design flaws which prevent it from achieving the full potential of constructive identity mediation. For one thing, there are many social constructs in our society which find their way, albeit metaphorically, into the game. Harell writes that video games often “support the argument that stigmatizing and socially constructive phenomena can be implicitly hardcoded into social computing systems” which ultimately result in “perpetuating longstanding social ills of discrimination and disinfranchisement” (pg 3). Such is the case in Mass Effect. Every race is negatively stereotyped and depicted within its own game world: Salarians colonized Krogans and think them to be stupid brutes, Asari are taken as sex icons, hanar are strange and sometimes unwelcome. Then again, we can’t quite tell if these social constructs are meant to be used to question our own social constructs–was this choice made with that particular intention? Or were they included because such constructs create a more belieavable world? If so, the game the writers seem to suggest that such constructs are an eternal, unchanging reality–even within completely fictional worlds. Such choices are more likely to disenfranchise players who are the metaphorical inspiration behind the constructs depicted in the game. Moreover, players who do not have the background to recognize the dialogue the game is trying to elicit may not even recognize what the writers are trying to do. Or more simply, some players may not care because of the common notion that games should only be fun, and not necessarily intellectually stimulating. Moreover, Mass Effect does a poor job of creating a believable game world. While you may have complete freedom to play as you wish, the “people” around you have terrible A.I. and are shackled to their dialogue scripts. Once you have talked to your crew members enough, they will forever be stuck in the last part of their script–no matter what is happening around them. For example, if you choose to romance Miranda, and end up sleeping with her in-game, every time you talk to her afterwards she still talks about how she’s looking forward to a moment that already happened. They didn’t program her to say anything after that, so she’ll just keep on repeating the same thing over and over again when you’re on the ship. Thus while all the decisions you make are very intellectually stimulating, they become noise you don’t pay attention to if you play through a second time. You already know what your choices and their consequences are. This is due to the fact that if you don’t like something that happened, you can simply reload and pick a better choice. Characters in the game never change, even though you might be playing a completely different Shepard from the first time. Exploring your identity through Shepard is only novel at first. Afterwards you realize that you don’t actually have much freedom to explore the complexity and fluidity of identity because the game world and its denizens remain static even if you do not. While games like Mass Effect aim to use identity and its complexities a part of its game mechanisms, video games are still a long ways off from exploring the subject in a meaningful way. Not only do limiting social constructs manifest themselves within the game, but so do limited AI and static game worlds. Still, games like Mass Effect 2 are a baby step in the right direction–if anything, while the real world may maintain ideas of normative identity, virtual worlds become a playing ground for us to break those rules and explore the possibilities. The way we see ourselves and each other is changing. What you can do–who you can be, more specifically–may be but simplistic mechanics within a game today, but they may also be partially reflective of how important multiplicity is in exploring who we are. |

Pingback: The Friday Post: Time to Do the Ham Song! « Nightmare Mode